Elite Competition, Local Extraction, and Social Unrest: Understanding Mass Protest in Authoritarian Regimes

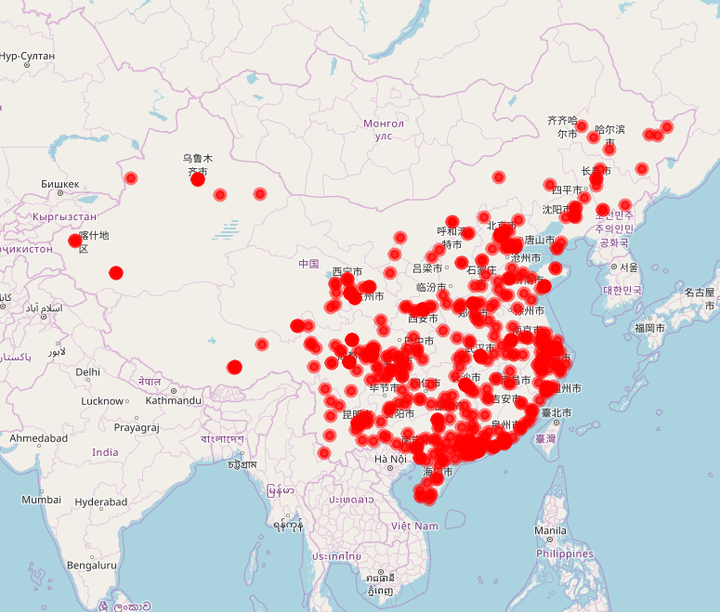

Why do we observe mass protest in authoritarian regimes? How can we explain subnational variation within a country? This study provides an institutional approach to explain mass protest in nondemocracies. I propose that the pattern of social protest reflects the intensity of subnational elite competition within authoritarian institutions. In China, the cadre promotion system incentivizes local elites to compete in the fiscal and economic field by extracting local resources, and these efforts often trigger local protest. Using a protest dataset that records large-scale local resistance from China, I find that Chinese social protest is associated with local elite competition in a nonlinear pattern. A rising intensity in local competition encourages greater extraction efforts and triggers more resistance; however, intensified competition does not lead to excessive extraction because officials fear that too much social instability could hurt their careers. I also find that land expropriation by local governments becomes the main extractive mechanism that triggers social grievance in contemporary China. These findings highlight the important role of competitive local politics and how it shapes the subnational variation of protest in authoritarian regimes.

菁英競爭、地方資源汲取與社會動盪-威權政體中群眾抗議的成因探析:

為什麼我們會在威權國家觀察到大規模抗議呢?我們又該如何解釋在同一國家內抗議的區域性差異呢?本研究從制度層面出發,探討非民主國家中大規模抗議的成因。本文認為抗議的模式可能反映了威權體制內部地方菁英競爭的強度。以中國為例,幹部晉升體系激勵地方菁英在財政與經濟領域展開競爭,透過加大擷取地方資源的方式提取來提升績效,而這類行為往往引發地方抗議。利用中國大規模地方抗議的數據,我發現中國的社會抗議與地方菁英競爭呈現非線性關係。當地方競爭強度上升時,官員傾向加大資源提取力度,進而激發更多社會抗議。然而,過度激烈的競爭並不會導致極端的資源掠奪,因為官員擔憂過多的社會動盪可能損害自身仕途。此外,本文也發現,在當代中國,地方政府的土地徵收成為主要地方資源擷取的機制,並構成社會不滿的重要來源。這些發現凸顯了地方政治競爭在威權體制中的關鍵作用,並揭示了其如何形塑不同地區的大規模抗議模式。